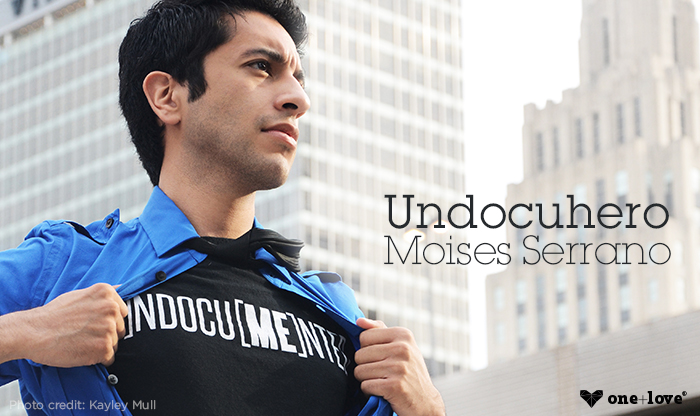

Undocuhero: Moises Serrano Bounds Over Barriers

Forbidden: Undocumented and Queer in Rural America offers a window into the undocuqueer movement through the life and lens of Moises Serrano. Directed by Tiffany Rhynard and Kathi Barnhill — with some filmwork from Serrano himself — the documentary captures the everyday feats of this undocuhero: at home with his partner, in the streets during political actions, and visits to his family in Yadkinville, NC. While the film is slated for release in December, webisodes and video journals offer glimpses into his organizing odysseys and more. And here are even more windows and wisdoms from Moises Serrano:

What has surprised you in your storytelling journeys across North Carolina? Did you get any reactions/responses that you didn’t anticipate?

I like to think of myself as someone who is not easily surprised. I like to prepare for every situation. However, on one occasion — when I was boycotting a documentary that was spreading hateful propaganda about immigrants, brought to a local community college by a county sheriff — my life was threatened by a local county commissioner. I look back and I realize how people are being indoctrinated to believe that immigrants are criminals through this anti-immigrant language, film, and print that has come to exist in our society. So in this county commissioner’s view, I was a criminal worth shooting.

What are some of the issues particular to being undocumented and queer? Undocumented in the U.S. South?

I think one of the biggest issues is the psychological warfare and its toll on LGBTQ and undocumented immigrants. We are a double minority that oftentimes has to face violence, bullying, and neglect from two different worlds and perspectives. On one hand, I was bullied through high school for being queer, and on the other, I have faced hostility and abuse for being undocumented. Oftentimes these situations lead the undocumented, queer, or “undocu-queer” population to depression and even death.

Growing up undocumented, Latino, and Mexican in the South has had a huge impact on my outlook in life. I have met some of the nicest, most genuine people in North Carolina, but I have also faced situations that have made me want to lose hope. One instance in particular happened when I was 9 or 10 years old. I woke up to hear a commotion on my front porch. I remember making my way outside where my family was on our cement porch looking down to the ground. There I saw a symbol that I didn’t comprehend at that age but later in life I would realize the full impact of its presence. It was a white cross made of white stones. The symbology was new to my parents; they have lived in blissful ignorance since that day for they still do not know what it means. My mother thought it was a sign from God, although I know that whoever placed that white cross in front of my home had no God in them. However, I am not the one to take that moment away from her.

How did/does it feel to “come out” on multiple levels?

Coming out on multiple levels was really hard. I came out to the world as undocumented years before I came out as queer. The hardest part was telling my parents I was queer, and on some level, it will always be that way. For me, I feel that being undocumented has a very simple solution. If allowed, I can go through a naturalization process, but as a queer man, I will always be queer for as long as I live. There is no cure, no fix, and no pathway to heterosexuality.

What fuels your organizing and truth-telling?

I am fueled as a storyteller by multiple reasons. Two that are predominant are my family and the stories of the community. My parents are heroes: they sacrificed everything they had, even faced death, just to bring me to this great country so I could have a piece of the American dream. I hope to one day pay them back for all they have done. Also, I often hear a lot of pain from the undocumented immigrant community. I hear stories of deportations, poverty, and police abuse. When I hear cases of injustice I believe it is my duty to help those in need. As Martin Luther King, Jr. once said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

One+Love is honored to be a partner for Forbidden: Undocumented and Queer in Rural America.

Recent Comments